When the Supreme Court significantly enhanced Second Amendment rights last year, the conservative majority said gun regulations could be upheld only if they had a historical analogue tracing to America’s founding in the late 18th century.

But what of a law that strips gun rights from people subject to domestic violence protective orders – when domestic violence wasn’t recognized as a serious problem back then? Not until the late 20th century did states widely adopt laws to protect victims of domestic violence and to hold abusers accountable.

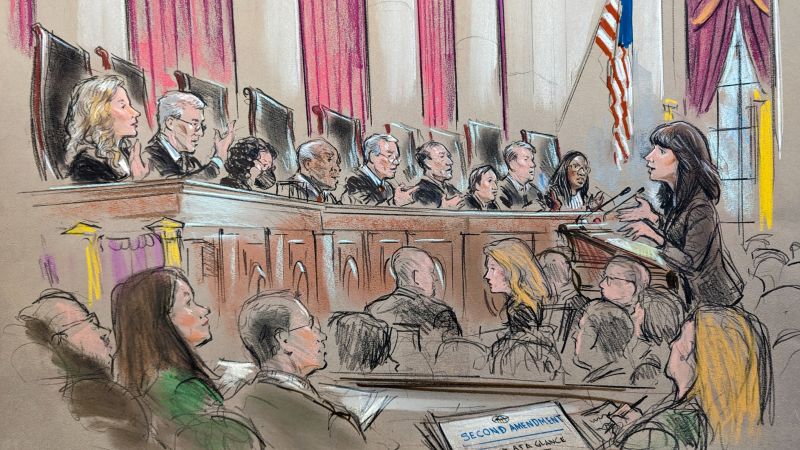

Faced with that reality during oral arguments on Tuesday, some of the justices appeared willing to try to clarify their 2022 milestone ruling that has confounded lower court judges and led to a raft of decisions invalidating firearms laws.

The problem of domestic abuse was in the air as much as any constitutional theory during the 90-minute session. And the nature of the case may guarantee not only that the federal government prevails but also wins some flexibility for judges searching for historical analogues in Second Amendment disputes.

To be sure, the conservative majority did not appear ready to abandon its core emphasis on the history and tradition that led to the Second Amendment in 1791. Rather, some of the justices who joined last year’s decision seemed to accept the federal government’s arguments that lower court judges were at odds over how to follow it, with many too rigidly interpreting the court’s mandate regarding the amendment’s original meaning.

The question now, however, is whether a majority can provide sharper guidance on this second round.

One of the most quoted – but open-ended – lines from Justice Clarence Thomas’ opinion last year in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen was that “analogical reasoning under the Second Amendment is neither a regulatory straightjacket nor a regulatory blank check.”

Earlier this year, the conservative 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals, relying on the Bruen reasoning, found no valid analogue for the gun prohibition on people subject to domestic-violence orders, declaring it “an outlier that our ancestors would never have accepted.”

Appealing that ruling, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argued on Tuesday that “Guns and domestic abuse are a deadly combination,” adding that “as this court has said, all too often, the only difference between a battered woman and a dead woman is the presence of a gun.”

Prelogar argued that the valid analogue in this case would be 18th century practices that kept guns away from people considered dangerous or “not responsible … like the mentally ill or minors.” She said 48 states have laws like the federal government that “temporarily disarm” people subject to domestic violence restraining orders.

She said the court need not “break new ground here,” but rather make clear the wide variety of historical sources and evidence judges can use when determining the scope of Second Amendment firearms rights.

“We think that you should make clear the courts should come up a level of generality and not nit-pick the historical analogues that we’re offering to that degree,” she said.

At least three of the justices from the majority in the 2022 decision appeared open to Prelogar’s analogue of “dangerousness.”

“So you’ve invoked the consensus among the states, the tradition of dangerousness, and I don’t think you’d get a lot of push-back because this is violence after all, domestic violence,” said Justice Amy Coney Barrett said, as she raised concerns about situations that would fall outside that “heartland.”

Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh also seemed inclined toward Prelogar’s arguments.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who was also part of the Bruen majority, challenged her reference to laws covering people who are “not responsible,” saying that could be “extremely broad.” But Roberts also sharply questioned the lawyer defending Zackey Rahimi in a way that again put a spotlight on the alleged domestic violence.

“You don’t have any doubt that your client’s a dangerous person, do you?” Roberts asked lawyer J. Matthew Wright.

“Your Honor, I would want to know what ‘dangerous person’ means at the moment,” Wright responded.

“Well, it means someone who’s shooting, you know, at people,” Roberts said. “That’s a good start.”

A Texas state court, after hearing evidence that Rahimi assaulted his girlfriend in an Arlington, Texas, parking lot and fired his gun at a witness, prohibited him from approaching or threatening the girlfriend and her family.

When Rahimi later became a suspect in a series of shootings, and weapons were found at his home, he was charged with violating the 1994 federal law that bars a person subject to a protective order from possessing a firearm.

The pending dispute, United States v. Rahimi, drew dozens of friend of the court briefs from organizations seeking clarity on the Bruen case, including many from advocates trying to prevent domestic violence. Those groups argued that the Bruen rationale lets judges take a nuanced approach to contemporary measures – even if there’s no exact historical analogue from the founding era.

Today, advocates for the prevention of domestic violence say, on average, 70 women are shot and killed each month in the US by their intimate partner.

Prelogar highlighted such statistics, as she told the justices, “A woman who lives in a house with a domestic abuser is five times more likely to be murdered if he has access to a gun. And it’s not just the harms in the home. It extends to the public and to police officers as well.”

Justice Samuel Alito, a consistent critic of the current administration’s positions, voiced greater concern for people who may be subject to restraining orders.

He questioned whether someone might face an order without “any finding of dangerousness” and then be barred from possessing a gun.

“Now suppose someone is later prosecuted for violating that provision,” he asked Prelogar, “would it be a defense for that person to say that the state law in question did not require such a finding and, in fact, there was no such finding in my case?”

Prelogar brushed back the scenario, essentially saying it would not interfere with the federal prosecution.

“We are told in some of the amicus briefs,” Alito later said, “that there are situations in which the family court judge who has to act quickly and may not have any investigative resources faces a … he said/she said situation, and the judge just says: ‘Well, I’m going to issue an order like this against both of the parties.’ Do you agree that that occurs?”

“No,” Prelogar responded. “I think that that is largely a mischaracterization of what is happening in the state courts day in and day out.”

Wright, representing Rahimi, seemed aware of the difficulty of his case and the cold reception from most of the justices, especially to the claim in his brief that, “The government has yet to find even a single American jurisdiction that adopted a similar ban while the founding generation walked the earth.”

“So is that what we should be looking for?” asked Justice Elena Kagan, who dissented in the Bruen case. “And if we don’t find that similar ban, we say that the government has no right to do anything?”

“I think that’s largely what Bruen says,” Wright answered, but then added, “I don’t think it has to be so narrow.”

He further equivocated when Kagan asked if Congress could “disarm people who are mentally ill, who have been committed to mental institutions.”

“I’ll tell you the honest truth, Mr. Wright,” Kagan said. “I feel like you’re running away from your argument, because the implications of your argument are just so untenable that you have to say, ‘No, that’s not really my argument.’”

As liberal Kagan continued, she addressed Wright. But she might have been subtly speaking to her colleagues who signed the Bruen decision.

“It just seems to me that your argument applies to a wide variety of disarming actions, bans, what have you, that we take for granted now because it’s obvious that people who have guns pose a great danger to others and you don’t give guns to people who have the kind of history of domestic violence that your client has or to the mentally ill or what have you. … You seem to be running away from it because you can’t stand what the consequences of it are.”

Read the full article here